Game To Lose

This page is based on a contribution from Mike Jones.

Introduction

Game to Lose is a three-player card game played in the West Midlands of England. It is a reverse version of Chase the Nine or Chaser (which is the local name for Nine Card Don), in which the object is to avoid taking tricks containing valuable cards.

The scoring of each hand is in two parts:

- some cards score immediate points during the play for the player who wins them in a trick, and

- at the end of the play the cards in tricks are counted using a different system of values and the player who has the greatest value of cards scores extra points.

Scores are recorded on cribbage boards, and the first player whose total score reaches 121 or more points is the loser.

Players, Cards and Equipment

This game is always played by three people. It is possible that the game evolved from circumstances where four players were not available for full game of “Chaser”.

A standard Anglo-American pack of 52 cards is used. The cards in each suit rank from high to low A-K-Q-J-10-9-8-7-6-5-4-3-2.

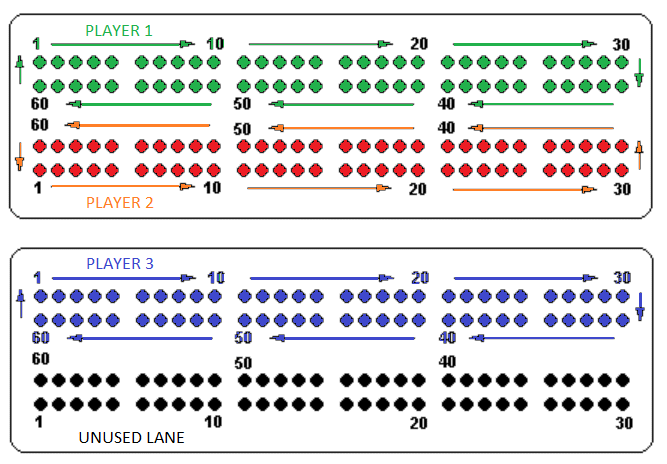

Since players score points throughout the play as well as at the end of a hand, it is convenient to use a pegboard or boards to keep the score. One way is to use three of the lanes from two standard crib boards, like this:

With the above arrangement, each player will make two circuits of the board to reach 121 or more points.

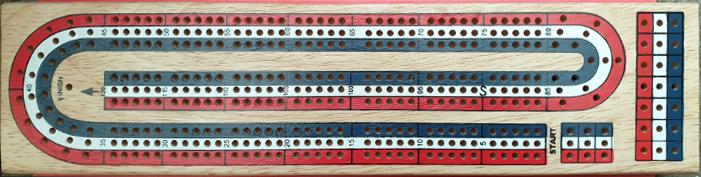

Alternatively, if available, a specialised 121-hole three-lane board may be used:

Deal

To choose the first dealer, the pack is shuffled, each player in turn cuts the pack, lifting a portion of it and turning it face up to show the bottom card. Whoever cuts the lowest card will be the first "Pitcher". If there is a tie for lowest card, the players involved cut again until a “Pitcher” is determined.

The deck is then reassembled by the player to the right of the “Pitcher”: this player will be the first dealer, after which the turn to deal will pass to the left after each hand.

The dealer shuffles the cards and places them face down onto the table, the player to dealer's right cuts the deck, lifting a portion of the pack, placing it on the table, and then putting the remaining bottom section of the pack on top of it.

The dealer then picks up the pile and deals four hands of 13 cards each, dealing one card at a time, clockwise. The first card of each round of the deal goes to the pitcher, the second to the next player, the third to the dealer and the fourth to a dummy hand. This dummy hand (which will be between the dealer and the pitcher as the cards are dealt clockwise) plays no further part until the next deal. It is set aside and no one is allowed to see what cards are in it: all cards in the dummy hand are “sleeping”.

Play

The Pitcher begins the play by leading any card, placing it face up on the table. The suit of this card becomes the trump suit for the hand (for this and the following 12 tricks). Each of the other players in turn plays a card, and the winner of the trick stores the three cards in from of them in their 'won' pile and leads to the next trick. Since it is only the cards won in tricks that are important and not the number of tricks taken, the 'won' cards can be kept in a single pile and need not be stored as separate tricks.

When playing to a trick, players must follow suit if they can, by playing a card of the suit that was led. A player who is unable to follow suit may play any card. The trick is won by the highest card of the suit that was led, unless there are trumps in it, in which case it is won by the highest trump.

If a trick contains any scoring cards, the player who won the trick must immediately peg the value of that cards or cards. The cards that score during the play are:

| Ace of trumps | 4 points |

| King of trumps | 3 points |

| Queen of trumps | 2 points |

| Jack of trumps | 1 point |

| Nine of trumps | 9 points |

| Five of trumps | 10 points |

| Other Fives | 5 points each |

No other cards score. So there are up to 44 points that might be pegged during play: 29 for trumps cards plus 15 for the other three Fives, but in practice there will usually be fewer because some of the scoring cards will be sleeping in the dummy.

If the points pegged by the winner of a trick take the player's total to 121 or more, the game ends immediately. That player is the loser and pays the agreed stake to each opponent.

Scoring after the Play

At the end of the 13 tricks each player counts all scoring cards in his “won” pile, according to the following schedule.

| Each Ace | 4 points |

| Each King | 3 Points |

| Each Queen | 2 points |

| Each Jack | 1 point |

| Each Ten | 10 points |

The scoring cards here are not the same as those that score points during the play. Tens are now important, Nines and Fives have no value, and there is no difference in value between trumps and other suits. The total number of points in the pack is 80, but nearly always there will fewer than 80 in play because some will be sleeping in the dummy.

The player who has most card points in their tricks according to this schedule pegs 8 points for "the Eight". If two players tie for most card points each of them pegs 4 points. If this pegging takes anyone above 120 points on the board that player is the loser and pays the agreed stake to each opponent.

It is rare but not impossible that two players tie for most card points, and pegging 4 points each takes both of them above 120 on the board. I suggest that in this case they have both lost (even if their scores are unequal) and that both of them should pay the agreed stake to the lucky third player who has not lost.

Another even rarer possibility is that all three players could have the same number of card points in their tricks. In this case I suggest that no one should peg any points for the Eight.

I would be interested to hear from anyone who has come across either of these unusual tie situations and can tell me how they are traditionally handled.